In most cases, collecting feathers in the United States is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), which prohibits the possession of feathers, parts, and eggs. But that doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to enjoy a feather-finding hobby.

Feathers and the MBTA

The MBTA was enacted primarily in response to the wholesale slaughter of birds for the use of their skins and feathers in millinery (hat-making) in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It prohibits the “take” (hunting, trading, transport) of most native birds and any of their parts, including feathers. Even feathers that are picked up off the ground are illegal to possess under the MBTA because it is near impossible to tell the difference between a naturally molted feather and one plucked off a poached bird.

MBTA Permits

MBTA permits only exist for a select few activities, with no provisions for personal feather collections. However, public educational and scientific institutions such as universities, museums, and zoos may be eligible for the long-term possession of feathers and other bird parts. Individuals wishing to salvage and possess feathers on a temporary basis before donating to an eligible institution might consider applying for a Salvage permit. Similarly, those conducting scientific research can apply for a Scientific Collection permit, with collected specimens donated to an eligible institution upon the completion of study. These federal permits are only valid if you also have the requisite state permits, so check what your state’s policy is as well.

Exempted Species

Certain species are not protected under the MBTA. These include introduced non-natives, non-natives not present in the US or its territories, and a select few natives. For the purpose of the MBTA, which is administered at a federal level, a species is considered native if it occurs natively anywhere in the US or its territories, regardless of whether it is also introduced and/or invasive elsewhere.

Native species not covered by the MBTA include members of Landfowl (order Galliformes) and Parrots (order Psittaciformes). However, these are typically subject to local hunting law or CITES, respectively.

Introduced non-native species include domesticated poultry (the source of craft feathers), feral Rock Pigeons (Columba livia domestica), House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). These species tend to be common and widely distributed due to their association with humans.

The “Migratory” part of the name is a bit of a misnomer. While the original justification of the MBTA had something to do with the idea that birds with no regard for state lines could only be adequately regulated at a federal level, the actual migratory behavior of a species is not an important factor in determining its status under the MBTA.

In summary, it is legal under the MBTA to collect feathers left by the turkeys that visit your yard, save molted feathers from a pet parrot, ask a neighbor with chickens or guineafowl for their molts (and eggs if you’re lucky!), catalogue the prettiest pigeon feather variations, and admire the iridescence of a starling feather.

Other Applicable Laws

The MBTA exists within a diverse landscape of wildlife legislation. Depending on the species and origin of a specimen, other laws may apply.

Lacey Act

The Lacey Act of 1900 prohibits the interstate transport of poached specimens. If you acquire a feather illegally in one state and take it across state lines, you could be in violation of the Lacey Act.

CITES

The Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species applies to the international import and export of endangered species. Review CITES when buying, selling, or otherwise exchanging feathers across borders.

Local hunting law

Waterfowl and Upland Game Birds, which include Landfowl and sometimes others like doves and rails, are typically regulated by state or county hunting laws. The killing and subsequent possession of such birds may require a hunting license and adherence to hunting seasons, bag limits, etc. Check your local jurisdiction for specific requirements and whether hunting law applies to feathers.

Alternatives to Collecting

Navigating feather law is hard. To avoid the need for a permit altogether, consider activities that do not involve the physical possession of feathers. Photography is legal and increasingly accessible with the advent of smartphones, and photo-sharing platforms such as Instagram or iNaturalist allow you to share your finds with a broader audience. I find that with my mobile phone, it’s usually a 20-second process to pick up a feather, photograph the front and back, and release it to the wind, leaving me with a digital souvenir that I can share and take anywhere.

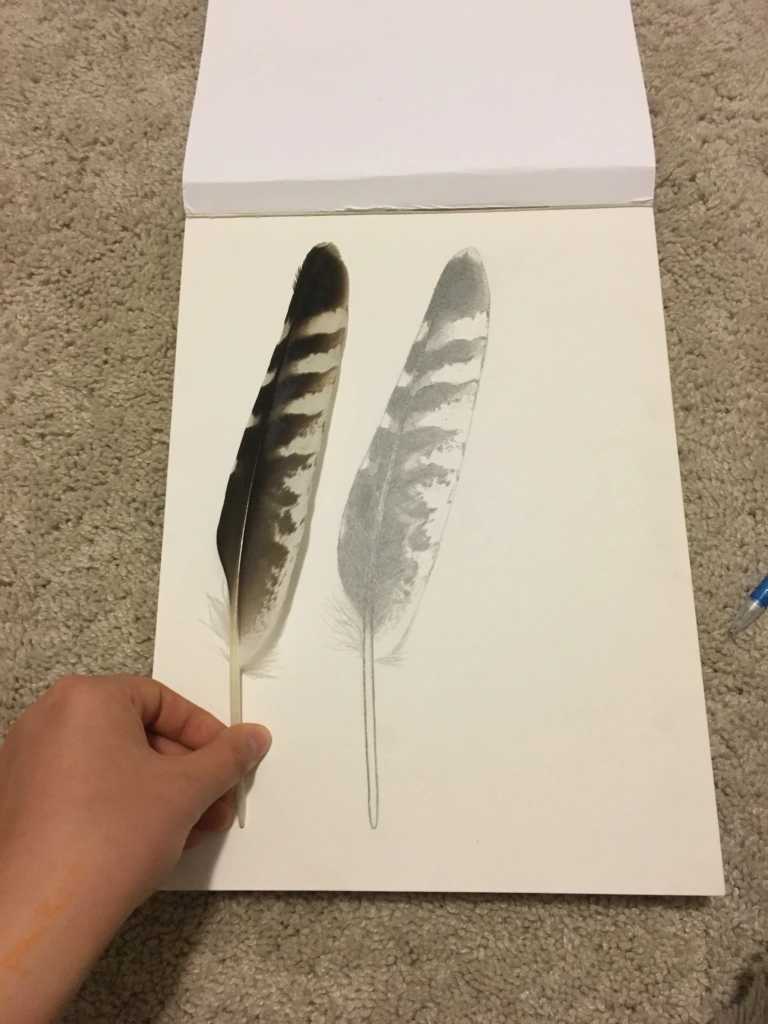

You might also consider nature journaling, if that’s your cup of tea. Fellow blogger Jean Mackay does a stunning job of capturing natural beauty with paint and paper, two feathery examples of which can be seen here and here. But all you need is a pencil and some patience.

Conclusion

While individual feather collectors may not seem like a great risk to bird conservation, it is important to recognize and reflect on the abusive heritage of collecting, in individuals like John James Audubon who shot the birds he painted (common practice at the time), Victorian “oologists” that snatched eggs from their nests, and endangered species such as the Kākāpō whose growing rarity once spurred scientists to hunt it faster. Not to mention Operation Silent Wilderness and similar modern cases that crop up with alarming scale and frequency.

Whatever your approach is to feather finding, respect towards wildlife and their natural habitats should always be your chief priority, as exemplified by the ABA Code of Ethics. There are good reasons for why feather legislation is so strict, and both small-time enthusiasts and seasoned amateurs need to work together to prevent the normalization of actually destructive collecting practices like poaching.

That said, good luck, and happy feather finding!

Further Reading

The Feather Atlas: Feathers and the Law

** Please note that this is not a definitive guide to all laws concerning the possession of feathers in the United States, and is merely an overview of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. My intention in publishing this article is to encourage and draw attention to the ways in which feathers can be interacted with in a respectful and legal manner. I am not a lawyer.

Edited 14 January 2023: rewritten extensively for tone, clarity, and accuracy; and 31 March 2024: added additional links to conclusion

As an ex Interpretive Services State Ranger, we would find and collect found feathers throughout the DNR lands to be exhibited and displayed in Lectures and programs to the public, organizations, and school’s, as requested.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this!! The first time I ever saw a White Ibis feather was at the Harris Neck NWR visitor center. Great teaching experience that I wish people could experience more often—thank you for sharing!

LikeLike

i like the feathers!

LikeLiked by 1 person